A FEAST FOR FLORA- UNA CENA PER LA PRIMAVERA 24th May 2021

On the wettest day of the year, we were nonetheless thrilled to welcome our first guests for an actual real-life Supper Club! Between foraging expeditions to Sant’Erasmo for elderflower, samphire, fig leaves and rosemary, wheeling a spare fridge over the bridges in the monsoon and a last-minute dash to transfer the garden indoors it was a little bit hectic, but for those of you who were able to come, we hope it was worth it. Below is the essay on Venice, flowers and Botticelli we presented on the night, and details of the menu below.

In the bottom right hand corner of Botticelli’s Allegory of Spring, a bunch of iris blooms at Flora’s feet. On the other side of the picture, where Mercury reaches for a golden apple, the god treads on a bejewelled carpet of flowers, but the elongated blue petals of the iris are absent. Primavera is a notoriously tricksy painting, not least because is demands to be read in the opposite direction- right to left- than that to which Western eyes are accustomed. There are nearly as many interpretations of Primavera as there are visitors to the Uffizi, many of them centring on Neoplatonism, that famous Renaissance term never used by the Renaissance, but the missing flowers lend themselves to yet another, one which connects one of the transcendental masterpieces of Tuscan art with the republic of Venice.

Irises just here above!

In 1422, the republic of Florence sent an embassy to Venice to propose the formation of a defensive league against the increasingly aggressive territorial ambitions of Milan. Characteristically, the Venetians prevaricated. They had no quarrel with Milan, they protested, they were traders, not warriors. The Florentines returned the next year, and the next, by which time the armies of Filippo Maria Visconti had overrun the Romagna, Genoa and Rimini. Exasperated, the Florentine envoy of 1424 threatened the Venetians with something they feared more than tides and pirates-monarchy.

“Signors of Venice! When we refused to help Genoa, the Genoese themselves adopted Filippo as their lord; we, if we receive no support from you in this our hour of need, shall make him our king.”

Republican values being as dear to the Florentines as they were to the Venetians themselves, this was not to be countenanced. The senate bestirred itslef, hired a famous mercenary general, Carmagnola, and embarked on the most ambitious land war they had ever undertaken. Florence was saved, Venice’s holdings on terra Firma expanded to their greatest-ever extent, and Carmagnola was ultimately found guilty of dereliction of duty, beheaded between the columns in the piazza and had his vast fee reappropriated by the state, which was most satisfactory and a saving all round.

By the time Botticelli came to paint Flora, however, republicanism in Florence had been destroyed from within, by the ascendant power of the medici dynasty. In 1476 Lorenzo “il Magnifico”, the de facto ruler of the city, inherited the guardianship of his two young second cousins, Lorenzo and Giovanni, and promptly helped himself to their fortune, acquiring in 1477 the Villa Castello, the house where Vasari records seeing the painting he called Primavera in the first extant description of the canvas, in his 1550 Life of Botticelli: “e cosi un'altra venere, che le grazie la fioriscono, dinontando la primavera”. The painting was for many years assumed to be related to the marriage il Magnifico arranged for his cousin Lorenzo in 1482 to Semiramide Appiano, daughter of the lord of Piombino, an appropriately elegant wedding gift for a fiscally and diplomatically lucrative alliance.

However, some critics suggest a later date for the composition of Primavera, 1485, the year after il Magnifico had barred Lorenzo from assuming any political office in Florence. If this date is accepted, the picture and its provenance might be interpreted quite differently, as a comment on Medici rule and, arguably, a political manifesto. In this reading, the commissioner is Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco himself, and the figures within it representative of cities with which Florence had history of both alliance and conflict. Flora is Florence, Mercury- famously inconsistent and unreliable- is Milan. Between them Venus, just off centre of the painting, stands Venice. The iris flowers in the bottom right are associated with the Virgin (the sword shaped leaves invoke Our Lady of Sorrows), an allusion which reaches back through classical mythology to the iris flowers being gathered by Persephone when she was abducted by Hades, ruler of the underworld. The rainbow goddess Iris thus became the figure who led the souls of young girls into Hades.

Considering the painting’s right-to-left axis, the two months of spring, April and May, are represented by Venus and Mercury, to whom those months in the Roman calendar were respectively sacred. Flora/Florence stands on the right at the beginning of the season, Mercury on the left, anticipating summer and the fruits of what has been sown. If the painting was commissioned by a disgruntled Lorenzo de Pierfrancesco and hung in the villa il Magnifico had forced him to buy, what is it saying about the progress of Florence from republican freedom to monarchical servitude? Venice had once before protected Florence from Milanese tyranny, and the motif of the iris, the fleur de lys, was frequently employed in the iconography of the Doges, her elected rulers. Will Flora/Florence be led into the underworld as Medici rule comes to fruition? Or must she seek alliances to protect herself?

(In the end, Lorenzo did just that- setting himself up as “il Popolano”, man of the people and the defender of the republic on il Magnifico’s death in 1492, and welcoming the invasion of the French to “liberate” the city.)

Politics aside, the meadow in which Botticelli’s gods and goddesses dance would have been familiar to fifteenth-century Venetians, as well as the Florentines. Buttercups, daisies and forget-me-nots still cling improbably to the stones of the campi and between the plaster of palazzo walls, the banks of Sant’Erasmo still blaze with spring poppies the cornflowers, “bachelors’ buttons’, traditionally worn by young men in love are still bright in the sandbanks of the Lido. Venice has many wonderful hidden gardens, but her flowers are also humble, almost invisible- the sea wormwood, toadflax, celandine, bogbean and cornelian cherry that cling to the bridges and the lips of the fondamente. Our menu this evening pays tribute to the alliance between Venice and Florence in a minor key, taking inspiration from the everyday flowers that became so hauntingly luminous in Botticelli’s hands.

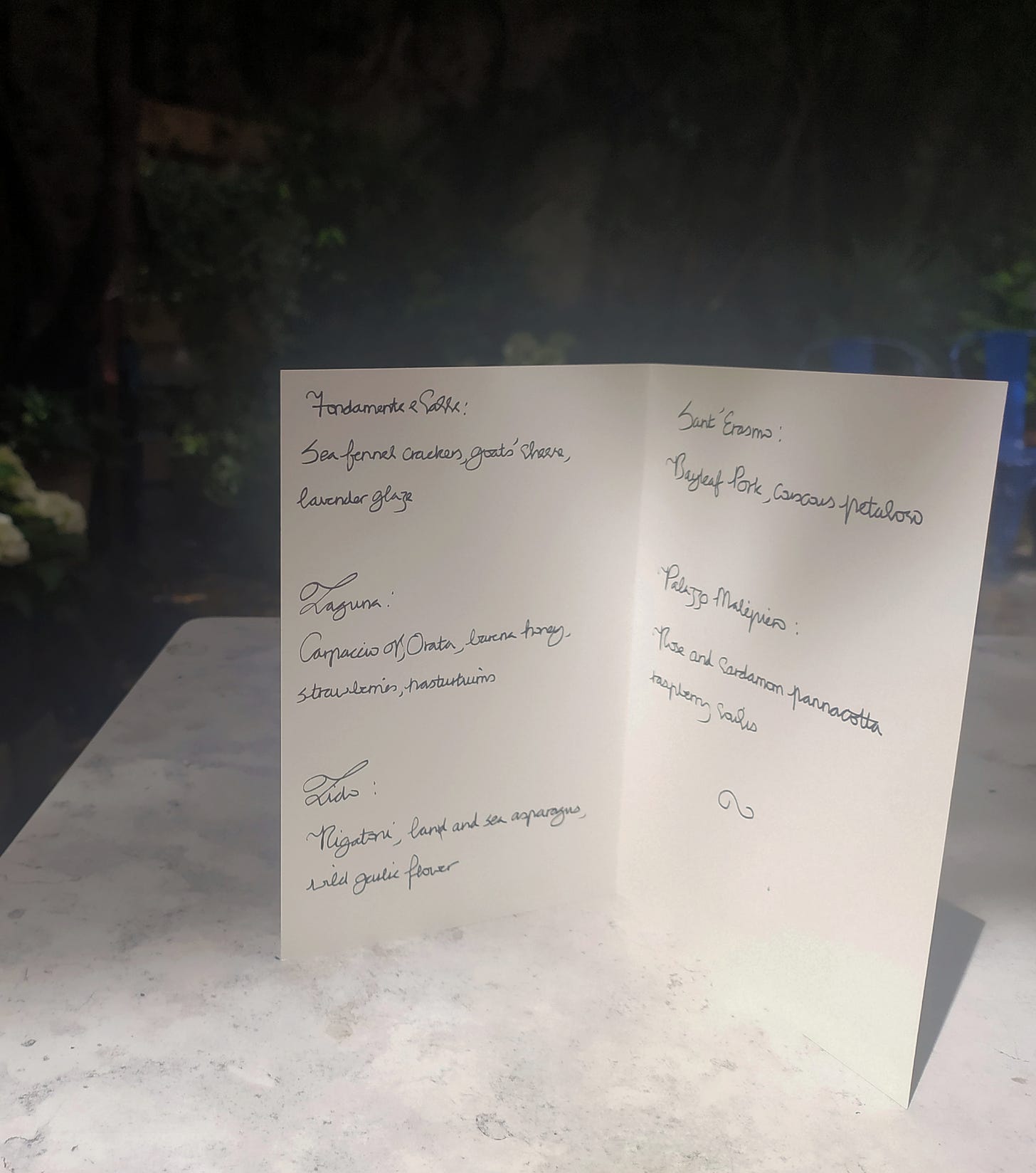

MENU

Nearly all the recipes that made up this menu can be found either in previous newsletters (linked) or below. We hope you enjoy a spring feast of your own!

Wild fennel crackers, with goats cheese, local honey and lavender

Sea Bream Capraccio with strawberries, radishes and nasturtiums

White Asparagus Rigatoni

Lemon and Mint gelatin palate cleanser

Bay Marinated Pork with petaled couscous

Rose and Cardamon Panna Cotta

WHITE ASPARAGUS RIGATONI

Serves 4

300gr Rigatoni or another large pasta that collects sauce

1 stock cube

300gr White Asparagus

30gr Butter

1/2 cup of white wine

Works well with a small handful of parmesan

We also added some salicornia (sea asparagus) that we had collected from Sant’Erasmo (very much optional). But toasted pine nuts also add a nice texture.

Peel the asparagus fully and then cut them in half, woody ends and all. Bring two pots of water to a gentle simmer, add a stock cube and 40gr butter and the wine to one and the other add a handful of salt. White asparagus keep their flavour when cooked slow so try not to let the water boil vigorously. Put the halves without the tips into the pot of stock and butter and cover. Then tie the asparagus tips together in a bunch and stand up right in the gently simmering salted water, ideally the tips will be above the water as they soften quickest.

Put a final pot of boiling water on for the pasta. Rigatoni takes about 15 mins on the pack we like to cook it for 13/14 mins and finish the rest of with the sauce.

After about 8 minutes, turn the heat off under the asparagus tips and turn them on their side in the water. Immersing the tips as we prepare the rest. When they have cooled, remove them and chop into 3 cm pieces.

Retain about a cup of stock and set aside before straining the asparagus halves. Return to the pan and blend fully adding a little of the stock liquid if necessary.

Drain the pasta and then add this to the blended sauce, add a very generous amount of freshly cracked pepper and then stir through the asparagus tips.

LOIN OF PORK WITH SESAME and BAY

We served 4 kg of this (Anna looked most attractive wearing it as a boa on the vaporetto), but 500g is generous for four.

500g pork loin, trimmed of excess fat

4 rosemary sprigs

6 bay leaves

4 garlic cloves, crushed

2 tsp sesame seeds

2 tsp dried oregano

1 large red onion

1tbsp brown sugar

large glass dry white wine

splash of Marsala

4 tbsp olive oil

salt and pepper

Pre heat the oven to 200. In a clean plastic bag, put the sesame, crumbled bay, oregano, garlic, rosemary and a good grind of salt and pepper. Put the pork in the bag, tie and leave in the fridge up to 24 hours. When you want to cook it, slice the onion and lay the pieces in the bottom of a roasting tin, then sprinkle over the sugar. Plop the pork and marinade on the top and roast for 45 minutes. While it’s in the oven, get out a sieve and a small saucepan, into which you pour the wine and Marsala, a board and a large piece of aluminium foil. When the pork is finished, wrap in the foil and cover with a tea towel. Drain the contents of the roasting tin into the pan through the sieve and boil until reduced by a third. To serve, carefully unwrap the pork and pour any juices into the thin, fragrant sauce. Slice about 1 cm thick and serve on a large platter with the sauce poured over.