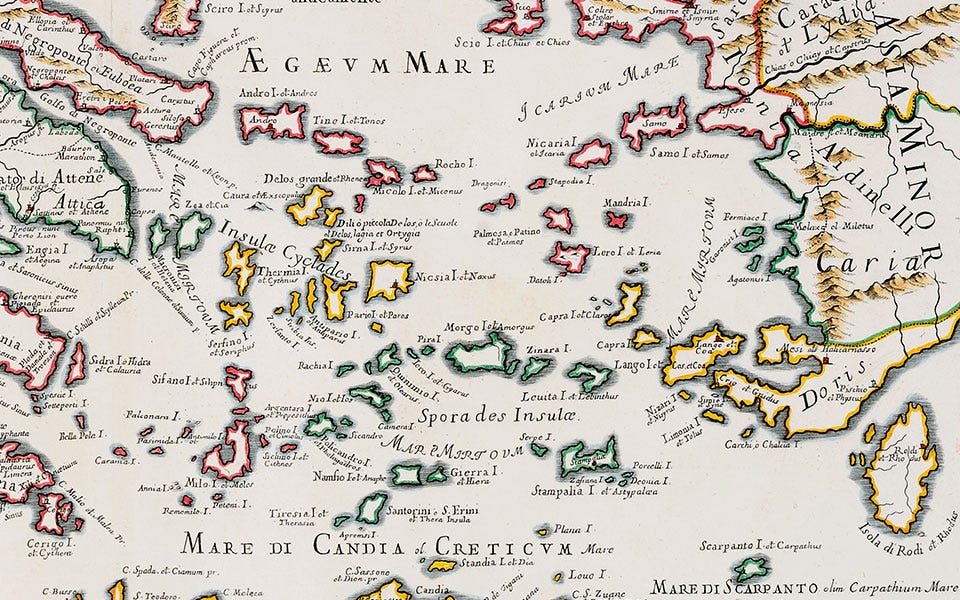

To the Venetians, the Dodecanese were always “The Archipelago”, the meandering ribbon of islands which stretch from the Dardanelles to the Sea of Crete. Venetian ships had been sailing the Aegean for a century before the Fourth Crusade, but after their forces under Enrico Dandolo sacked Constantinople in 1203, the sea was formally ceded, becoming part of the Stato del Mar of the nascent Venetian empire. Much to their chagrin, they never got their hands on the great island of Rhodes, which was given into the protection of the Knights of St John, but wherever you go in the Aegean islands, the presence of La Serenissima can still be felt. Almost every island has its ruined Venetian castle, whilst sponges, for centuries one of the chief exports of the region, are still known as enetikos- Venetians.

The system of government of the Aegean was , to say the least, informal. The Archipelago resembled the backwaters of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, a destination for unruly younger sons and ne’er do wells. The lords of the islands owed their formal allegiance to the Doge, but each was a miniature kingdom where life for the ruler passed as ‘a game in their sunlit, storm-swept fiefs”. Occasionally they had a little war between themselves to pass the time, pitting toy fleets and miniature armies against one another (Symi and Tinos gave battle over a donkey). The Greeks hated the Venetians at first, since they were less tolerant of the Orthodox religion and couldn’t be forgiven for the Crusade, but apart from egregious instances such as the ruler of Serifos, Niccolo Adoldo, turning pirate (frustrated with a lack of tax revenues, he kidnapped the island’s notables and held them for ransom. When they pointed out that they had nothing to pay it with since he had already relieved them of all their money he threw them off the ramparts of the castle), the Archipelago slowly adapted. Venetian was the official language and can still be heard in the odd word- most notably when it comes to food.

The Dodecanese were occupied a second time by Italians in the war of 1912 with Turkey. The Kingdom of Italy was supposed to return them, but never quite got round to it, and Italian they remained until 1947. Venice finally got her foothold on Rhodes, appropriately enough in the Venetian-style building which is now the Casino. The brutality of the second occupation has certainly been thickly plastered over with charm ( pace the Oscar -winning film Mediterraneo , shot on the tiny island of Kastelorizo), but there is still an affinity between Venice and the Archipelago. The harbours of Symi and Kastellorizo even look Venetian with their colourful, neo-classical buildings. Smart Venetians have summer houses on Symi and Astypalea and girls wear furlane with their bikinis. Perhaps it’s because you need to be able to handle a boat to enjoy the unparalleled waters of the rocky, often beachless islands, or perhaps it’s because of the food.

Curiously, if you want a taste of traditional Venetian cooking, you can still find it here- the Venetians introduced saffron and cumin, makarounes (pasta) and soumada, the almond drink of Nisyros which is made identically to the cooling almond- milk recipes suggested by medieval Venetian recipe books. Seafood is stewed with wine and spices rather than tomatoes and katoumaria, the nutmeg-dusted biscuits served at baptisms and weddings, are identical to the hard-wearing Venetian pevarini. Pastitsio was patriotically claimed for the Greeks by a French-trained chef, Nikolaos Tselemontes, who included his recipe for lasagne with béchamel sauce in his classic Greek Cookery of 1910, but the name and the dish are indubitably much older, and in Venice lasagne is still pasticcio, our recipe this week.

(Lisa writes- oh dear, photo below is by me. It tastes nicer than it looks)

SUGAR STREET PASTITSIO

Pastitsio can be scrumptious, but it’s often disappointingly bland and stodgy. Our version omits the béchamel and plays with a sauce based on the Greek stews- stifado- where intense, winey flavours compensate for a frugal use of meat. The sauce works well on its own with pasta if you prefer to omit the baking stage, in which case you will need to reduce the liquid for longer, though it should still be quite “wet”.

Ingredients for 6:

400g lean beef, cut into small chunks

1 large red onion

4 cloves garlic

2 sticks celery

1 large or 2 small carrots

1tbsp oregano

1 tbsp ground cinnamon

1 tsp sesame seeds (optional)

2 tbsp tomato puree

half a bottle red wine

200ml chicken or beef stock

Salt and black pepper

500g short pasta eg penne

250 g mozzarella

2 handfuls dried breadcrumbs

1 handful grated parmesan or Grana Padana

2 tbsp olive oil

Chopped parsley (optional)

Stage 1

Put a big pan of salted water on to boil and preheat the oven to 180. Finely chop the onion and celery, chop or grate the carrots and crush the garlic, then fry them all slowly in a pan which has a lid the olive oil. When they have some colour, add the meat and stir until browned on all sides, then add the wine, stock, tomato paste and spices. Be generous with the black pepper, it’s very much a note rather than a background in this dish. Cover and simmer on a low heat for about an hour. Meanwhile cook the pasta for 4 minutes less than the packet instructions (or 1 minute less if you are serving this as a sauce).

Stage 2

Mix the pasta and the sauce- it will be very liquid, but this will be absorbed during cooking. Tip into a large flat oven-proof dish and cover with a layer of breadcrumbs, then the mozzarella and grated cheese. Bake in the oven for about 20 minutes until the crust is nicely browned and bubbling. Leave to stand 10 minutes before serving and sprinkle with chopped parsley. This is lovely with a simple salad of sliced fennel with salt, oil and a little orange juice.